In the days before I knew I was a landscape painter I encountered Neil Welliver’s work. It is difficult to say to what exact degree his work influenced me, but my interaction with his large landscapes of Maine was the first time that I really thought about landscapes possible role in post-modern art. Now, one of my life goals is to explore what landscape painting can mean and to challenge the traditional concept of landscape painting and how we see landscape in our own lives.

In the days before I knew I was a landscape painter I encountered Neil Welliver’s work. It is difficult to say to what exact degree his work influenced me, but my interaction with his large landscapes of Maine was the first time that I really thought about landscapes possible role in post-modern art. Now, one of my life goals is to explore what landscape painting can mean and to challenge the traditional concept of landscape painting and how we see landscape in our own lives.

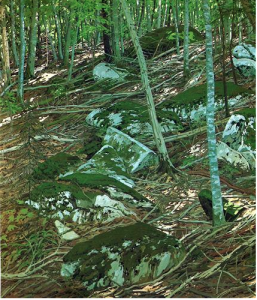

Neil Welliver is most famous for his landscape paintings of Maine. This, predictably, is the work that I am most connected to of his and the work I stumbled upon when it came to the Cabrillo College Gallery in 2000. It is always an amazing difference between seeing a work through media verses your own eyes. There’s a presence and a sense of color that just doesn’t exist the same way. With Welliver’s large format paintings there’s also a confrontation that happens while face to face with one. Welliver himself spoke of the aggression.

But really, my interest in painting lies in the fact of the painting. And I think that’s why sometimes people find the big paintings uncomfortable. Because they, in fact, perceive the space, sense it, and at the same time are repelled by the aggression of the painting, of the pigment, of the fact of the picture, its size. And it’s the same in the small ones. It’s absolutely the same in the small paintings, it’s just that it is less aggressive, easier to digest there. People who object to my painting, and they do, object very often to the aggression of the fact of the picture. They find the canvas, that surface, what happens on there, too much for them. They would really prefer to drift off into Bierstadt or someone, Corot, or something like that where you can really just enter into it and leave. With mine, there is the resistance of the surface of the painting. The fact of the painting is always in the way.

As we know there has been a debate in painting (for about 150 years now!) that painting is dead. Artists acknowledgment of this in the modern art period allows the post-modern painters a freedom of expression that has never before existed. For Welliver, the push and pull between paint itself and representation what he was interested in and landscape painting was the vehicle which he used. While interested in preservation, the landscapes are secondary to this dichotomy that he explored.

Many people feel a coldness from Welliver’s landscapes. This is partly due to the quality of the light in Maine, being such a northern location. It is also due to his study of color. He was very interested in colors, and greatly influenced by Josef Albers, whom he had studied under at Yale. Welliver’s approach to color was based on recreating the role of that color and exploring the middle values of color, to where the hue and not so much the contrast plays the majority role.

I’m most interested in color where the light is very middle, not in the intense sunlight and not in the darkest dark. Because when the light is very middle-ish, not intense nor reduced, it’s brightest and richest and to see those very small differences in the relationship between greens, that some are darker and some are brighter and some are bluer and some are greener. To be able to see these relationships and paint them and so on is central to my interests.

He acknowledged that color changed. That if you recreated the color exactly as it was on the leaf and brought it into the studio that the color was different and that it had lost the color of the presence of the air and the light that it had been surrounded with and that it was much more interesting to create a great color that preformed the role, rather than the color you saw during a on-site study.

I’ve eliminated all of the earth colors from my palette. I’ve eliminated them because there is a luminosity I’m after, that I can never find in those colors. I prefer to mix something which is their equivalent which is, for me, more luminous. (…)

But I never, never try to copy the colors out there. If I mix a color and put some of it on the object I’m painting, on leaves for example, I have done that before, it always looks bizarre. I’m not interested at all in ‘painting from nature’. (…)

I am much more interested in finding a color that makes it look like it is, again, surrounded by air.

To me, when I read these words I thought, “Ah-ha! These are the words that I have been grasping for when people ask me why I am not a plein-air painter and why I work in a studio when I am painting nature.” There is a greater truth in admitting the lie of representation.

Beyond the theory, his work has also had a more direct and obvious influence on my work. The most recent having been on my painting “Fall Creek Light”. As other artists do, I look to others when I get stuck. Earlier this year I was stuck while painting the water portion of “Fall Creek Light”. I turned to Welliver’s work to look for a solution. At an art festival this summer a gentlemen remarked, “Do you know Neil Welliver’s work? The water in the piece reminds me of his Maine landscapes.” Yep.

Beyond the theory, his work has also had a more direct and obvious influence on my work. The most recent having been on my painting “Fall Creek Light”. As other artists do, I look to others when I get stuck. Earlier this year I was stuck while painting the water portion of “Fall Creek Light”. I turned to Welliver’s work to look for a solution. At an art festival this summer a gentlemen remarked, “Do you know Neil Welliver’s work? The water in the piece reminds me of his Maine landscapes.” Yep.

All Neil Welliver quotes are taken from:

Jacket 21, Feb 2003, Neil Welliver in conversation with Edwin Denby